Sponge Tests

- Futch Press

- Oct 29, 2025

- 13 min read

E.K. Myerson

![Angel bearing a sponge, by Antonio Giorgetti, with the inscription “potaverunt me aceto” ("they gave me vinegar to drink", Psalms 69:22), western side of the Ponte Sant'Angelo à Rome. © Marie-Lan Nguyen / Wikimedia Commons / CC-BY 2.5 [2]](https://static.wixstatic.com/media/f8c883_759d24b7106e49709231f10b62f7eb3c~mv2.jpg/v1/fill/w_980,h_1470,al_c,q_85,usm_0.66_1.00_0.01,enc_avif,quality_auto/f8c883_759d24b7106e49709231f10b62f7eb3c~mv2.jpg)

These are swabs, fragments, some kind of remnants of a text which have had to seep through the loose edges of a self which has, due to present circumstances of mental breakdown, become porous.

The Holy Sponge appears in the corners of most scenes of the Passion. A medievalist still, I have written these descriptions with the windows of reliquaries in mind: slight crystals fracturing the scenes, aiming to make visible something that exists outside the mind, so that it can be kept safe here, within the mind.

1. The Sponge is for pilgrims

This is the Holy Sponge: it was offered to Jesus on the Cross. Soaked with vinegar and gall, Christ turned away his face. He was thirsty and the sour fluid tormented him, refused to relieve his distress. He was sweet, the wounds in his sides leaking the fragrant cure which becomes the Eucharist during the Mass ceremony. Vinegar appears as the antithesis of all that sensual transcendence: sour grapes to Christ’s sweet body. Positioned on a staff, a reed, or a pole, the sponge ascended and was rejected – or ascended and was bitterly received. In the aftermath of that event the sponge was translated, by which I mean it moved, like other relics, around devotional networks. It was taken from Jerusalem to Constantinople, and when Constantinople was sacked by crusaders, it was taken to Paris.

In one fifteenth-century Bohemian manuscript of the Travels of the (probably fictional) Sir John Mandeville, the scene of the translation of the relics to Constantinople is represented in grisaille.

![Presentation of the Passion relics from BL Add. MS 24189, f. 11. [1]](https://static.wixstatic.com/media/f8c883_5634fe86c2064d8984a6a1206e7464e4~mv2.jpg/v1/fill/w_823,h_1024,al_c,q_85,enc_avif,quality_auto/f8c883_5634fe86c2064d8984a6a1206e7464e4~mv2.jpg)

The King's crown and robes alone are highlighted in gold (BL Add. MS 24189, fol. 11). The strip of sky at the top of the scene is gradated blue: azure, like the Virgin’s robes. The sponge is held aloft on a split reed, jutting above the cross, which here is shown as a T, like the T-bar in the T-O maps which in the Middle Ages were used to represent the globe. The sponge is oval, soft-edged and the rupture of its surface by the reed is easily imagined. The tonsured monk who holds the reed is at the back of the group. The sponge is just off-centre in the image, but held in front of a central panel in the ornate church, the Hagia Sofia which forms the immediate background of the image: the church in which the sponge is to find its home, for now, before the Fall of Constantinople, before its secondary journey to Paris. The scene is solemn: the arrival of the sponge is met with reverence.

The Holy Sponge was less revered in medieval England than the other signs of the Passion. No known traces of the Sponge were translated to the British Isles in the Middle Ages. To replicate the Sponge seems to have been more difficult than to replicate fragments of the Cross, blood-stained earth or wood. The vegetal Sponge was self-reproducing, growing in the seabed and harvested for use in surgical procedures, but as a relic, the Sponge if anything, diminished. It was brought from Jerusalem to Constantinople and from Constantinople to Sainte-Chapelle: the glass reliquary of the cathedral housed the Sponge alongside the Crown of Thorns. So it was holy, holy, holy. But the Sponge did not travel well on its own. When removed from the group of the Arma Christi, its ambivalence was too challenging, it did not go anywhere. Its organic nature alone does not explain its disintegration as holy object in the imagination. Human body parts rotted away inside crystal windows across Christendom. There was something illegible about the sponge.

Later, the sponge became stone, a sentinel watching over pilgrims. One of the seventeenth-century statues on the bridge which joins the Vatican to Rome preserves the sponge in marble. Antonio Giorgetti’s sculpture has a strange affect now, especially when removed from the sequence of more familiar sacred iconography. The sponge is rectangular, the pole is ridged. It looks like the angel is going to clean the windows. The holy squeegee. It is too functional and too useless to be a respectable relic. Too useless when compared to the nails, too functional when compared to the Crown. The ripples of the angel’s robes and their hair, the large feathers which make up their wings, the soft bend of the finger which is crooked to keep the pole upright – the sponge sits oddly in the middle of these more normative Christian signs. It arrives in Rome from a commercial for cleaning products. You can imagine the satisfying sweep of its textured rim over a dirty floor, and the stereotypical, low-key smile of the person in the advert as order is restored to the domestic sphere. The sharp-edged removal of brown residue, absorbed magically into the sponge’s interior, taking the unclean from the world, one mop at a time, meeting dirt with synthetic power to cleanse. The sponge is the anti-grime. But at the same time, in the Christian scene the sponge is anti-Christ, the antithesis of cleansing. It is Christ who mops the world free of sin, absorbing the dirt of human suffering. It is Christ who is the Physician. It is Christ who is the sponge.

In one medieval representation, the sponge is pointed towards Christ from the right, while the spear juts directly into his side from the left. In this image, scale is out of joint: the nails are hammered into Christ’s palms by miniature figures who stand on the decorative borders of the frame of the image (BL Add. MS 38116) [3]. The figure who holds the pole on which the sponge is positioned is larger than these marginal hammerers, but less than half the size of the Cross. The sponge is proportionate to the scale of Christ: around the same size as one of his pecs, which are faintly shaded. The haziness of scale reflects the disjuncture of time in the Passion, which for medieval devotees occurred and still occurs: past and eternal. The gilding of the backdrop catches the light, the outlined Christ crooks his hip towards the heavens. The spear achieves penetration: Christ bleeds. But the rounded sponge stops just beneath his armpit, unable to rise to his face. Here Christ’s face is angled away from the sponge – towards the spear, towards unconsciousness.

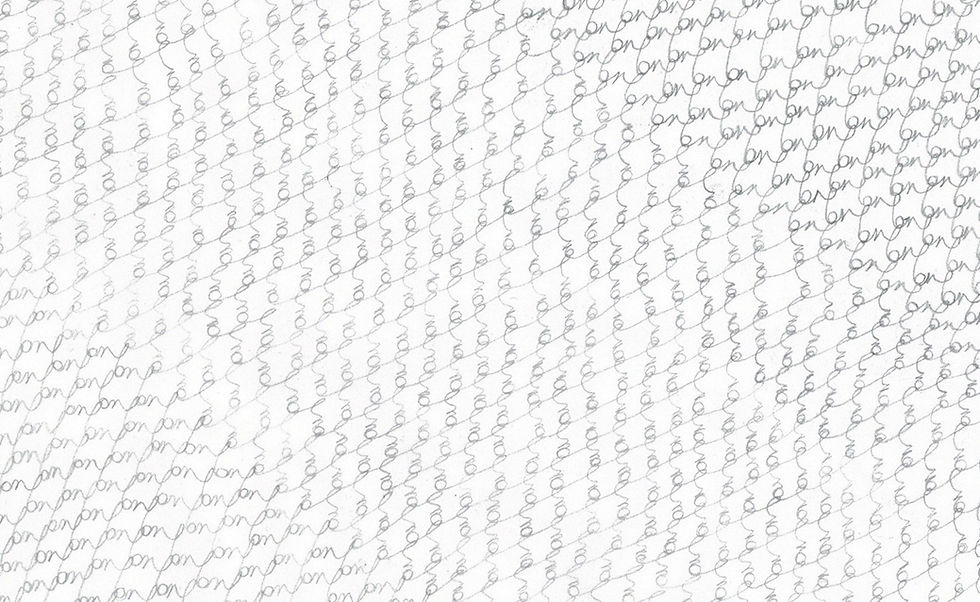

In one pencil study made after Giorgetti’s Vatican bridge statue, the artist has drawn the sponge in charcoal [4]. It has lost its sharp edges. The angel’s eyes downturned sadly, their soft wrist bent in what seems like a kind of hyperextension, the foreshortening of the wrist not quite executed to full realism. The robes ripple in coral waves and the neat, feathered wings match their transposition into stone, the pole appears as it becomes on the bridge. But the sponge is ethereal – the grey is bluish over the yellowish-brown surface of the paper. It isn’t that these gentle strokes can’t be carved or cast easily – they could be like the curls in the angel’s hair, not as soft as on paper but not square either. When the sponge moves from the page to the bridge it hardens and moves out of time, out of the sequence of memory and into a strange in-between time: sponge o’clock. Viewed in this way, the Holy Sponge is too modern and too medieval to be either: both, neither.

2. The Sponge is for patients

In the narrative of the Passion, the Holy Sponge is ambivalent. Unlike the nails, for example, which have the straightforward function of suspension and punishment, pragmatic objects used to fix Jesus to the Cross, the Sponge, being drenched in vinegar, absorbs the ambiguities of that fluid. In biblical and medieval times, vinegar was commonly used in medicine. Sour drinks were given to patients who had undergone bloodletting. Vinegary ointments were applied to ulcerous skin. As a corrosive, vinegar had a significant role in preventing infection. These sponges brought relief, pre-anaesthetic, acting on the sore. So, the vinegar on the sponge was not necessarily punitive. Those familiar with the surgeon’s table would have seen these images in light of that awareness of the vinegar sponge as a necessary, desirable object in times of dire need.

Even within the Passion narrative, the vinegar can be seen as a sour medical drink. In one medieval medical manuscript, a sponge is given almost a third of the parchment leaf, textured in brownish lines: ‘la sponga marina’, the sea-sponge (British Library Egerton 2020) [5].

The wounded Christ might need a sponge of vinegar: bleeding openly, nail-marked and pale-faced. Premodern viewers would have received these aspects of the sponge readily, knowing these treatises, viewing the sponge and its contents as desirable and proximate.

In one thirteenth-century manuscript, the Picture book of Madame Marie, the sponge is given pride of place. The viewer’s eyes are drawn to the sponge through its position, in the middle of the image following vertical lines, and on the line between the top third and the centre, following horizontals (Paris, Bibliotheque National Francais MS 16251, fol. 38r) [6]. It is brown and misshapen, stuck to the end of a thin rod. The conical-hatted person who offers it up wears a gentle expression: not sneering or caricatured like most of the Jews in medieval scenes of the torture of Christ. This could be a doctor. He stands behind the cross but his arms reach in front, offering up the sponge. The thieves are either already dead or are not judged worthy of an oral sponge-bath. Positioned in this way the sponge is designed to draw our attention, our sight – Christ, dying, has his eyes closed. His head is slumped and angled towards the sponge, but it stops short of his clipped beard.

3. The Sponge is Jewish

When moralised in Christian commentaries, the bitterness and its context combined to give the sponge the savour of Jewish guilt: the wooden staff pointing towards the face of Christ in a sour gesture of envy and retribution. To medieval Christians, Jewish bodies were seen as vinegary: an excess of melancholy made Jewish men’s blood thick. Accordingly Jewish men were thought to bleed monthly, a myth of male menstruation which was the backstory behind a number of blood libels. The idea was that the removal made Jewish men need to replenish their blood with that of Christian children. Pogroms followed in the wake of that story, of bloodthirsty vinegary Jews.

My own melancholy runs thick between my ability to put these words onto my screen into the order which I would like them to appear in. My former therapist would draw a link between my Jew–ish heritage and that inclination, although the link between these scenes and my own condition is indirect at best. My grandfather, a Jewish doctor, arrived from South Africa in 1948, my grandmother, a Jewish mother, followed him. Filling in the gaps between these histories is fantasy. I never knew my grandfather: he died from leukaemia when I was a baby. But I was told that he used to spend days sitting in a dark room. If I move my jaw to-and-fro I can almost hypnotize myself to sleep: my feelings come to the surface in some way through that movement and become unbearable in a conscious state. My grandfather painted and had the occasional exhibition, but he was not an artist in the way which, as the story has been told to me, he wanted to become.

4. The Sponge is for Artists

As a tool, the sponge is common in painters’ boxes, resting on the sides of palettes. Travelling towards and away from its origins towards a different mode of production, the sponge became inky, a stain on limners’ craft tables. The sponge was harvested in order to manifest scenes, dampened to receive and transmit shades for shady conceptualisation. Daubing and dotting texture onto animal skins. I can imagine its plastic, that is, moveable sides rubbed over a skein, a roll, a wall, leaving its imprint on the future in the form of a replicable tincture, a tint.

In one Flemish Book of Hours, known as the Rothschild Hours after its nineteenth-century owners, the instruments of the Passion are stacked in the right-hand margin. They rest in an open casket (BL Add. MS 35313, fol. 209r) [7]. The background is blue, but the effect is not to raise the scene towards the heavens. Even painted in that colour, the room is definitely an interior, not a horizon. A pillar at the left-hand side casts a shadow onto the azure wallpaper. The arrangement of the instruments is irreverent. It looks like the backroom of a stage production: as if these were the props for a performance, which they often were, in medieval dramatic renditions. The sponge rests against a column on a slim rod: round with a third removed. It now needs to be labelled to be recognised as a sponge, unlike the spear, or the ladder, which easily speak for themselves. It looks like a fan-headed paintbrush. It is a paintbrush, holding these colours up to sight.

The process of printmaking originated in the action of acid on an easily bitten surface. The vinegar which the sponge held became the material substance with which woodcuts became etchings, carving became metal plates in which images were drawn using biotechnology. The micro-organisms which acted on wine and turned it into vinegar left a powerful property in that fluid, which could itself act, continued to act. Artists left vinegar on copper sheets until the image sunk into the lines.

In a sixteenth century etching by Orazio Farinati, a group of naked cherubs carry the Arma Christi [8].

Their toes tread on the clouds. The Cross is geometrically precise, the hatching showing shade on clean edges, no traces of blood, the wood undamaged by its use. The whip trails over its edge, the crown of thorns is woven loosely. The sponge here is clamped between the lips of a split reed to the far right of the image. Here the pressure of the reed causes the clamped edge of the sponge to compress, the un-held side fans out. The clouds are watery wave-like in the combed movement of the lines beneath the cherubs’ feet. The acidic edges of the plates which were used to make this etching exist in the historicised backdrop of the scene, the apparatus discarded but remembered as a trace in that which it was used to make.

5. Sign-sponge

The property of ambivalence, which the sponge possesses in the scene of the Passion, is also possessed by sponges in other contexts. In his work Signsponge, a response to the works of the poet Francis Ponge, Jacques Derrida writes: ‘In keeping with a certain traditional phantasmatic tendency, you might say that the sponge is a feminine figure: passive matter [...], finding its liberty and its irreducible force in a passivity without limit, absorbing everything, good water or bad. It is a remarkable figure of a receptacle, of writing, for example, like the page or table on which he writes’. Beginning as a game played with the name of his interlocuter, the sponge is brought into material reality in these lines. It is tangible, fungible. If it was left damp it could grow fungi, like other forms of writing which left to themselves will form the ground for strange organisms, growing out and in between the fertile spaces of a base layer. Gendered in this way, the sponge engenders in others a curiosity, a resistant desire to become that which cannot be contained within the limits of current positions of societal relation. He goes on: the sponge ‘can also become [...] an hermaphrodite’.

The sponge is marred, meeting the lips of the always Holier sign. Except: does it ever get to the mouth? In the Fitzwarin Psalter, the sponge and the spear both arrive from the same side [9]. The sponge is light-hued and again nestles beneath Christ’s armpit, while the spear’s tip breaks the skin between his ribs. The spear can enter the body: through force. To show Christ accepting the sponge would be taboo. In the scenes of its procession, the sponge is airborne, like the other instruments. As it figures in scenes of the Passion, the sponge is typically at a slight remove from the sacred face. That speaks of queer desire in some way, at least to this reader, the strange object hovering nearby and refusing to become palatable, remaining shameful.

In medieval alchemy, vinegar was sometimes known by the name Mercurius, an in-between substance which was used to create the elixir. Also known as the androgyne, Mercurius combined male and female elements, that property of ambivalence making it a transformative material. The sponge in the Passion is not alchemical: but alchemical matter drips out of its edges, exceeds its primary function, surpasses and falls short of its purpose.

I remember, when I was a child, I was a boy – I always said so. This morning, walking down an avenue of trees, I saw steam coming through a vent into the air cut by the shadow of the wall which the vent was set into, the rest of the steam was white and the steam behind the shadow was invisible: clean line, white steam coming out of thin air.

6. Afterlife of the Sponge

Picasso included the sponge in his scene of the crucifixion, painted in 1930 [10]. Here the sponge is enormous, green with blue and orange tints – reflecting the blues and oranges of the scene towards which the sponge faces. Reflecting and absorbing the palette of the rest of the Passion, the sponge also appears in contrast, green against orange, hovering. In Picasso’s version, there is no pole. The sponge floats up and away from the event: the catastrophes of the twentieth century. Unmoored, Picasso’s sponge remembers that which followed his representation, contemplated as an artefact of premodern and modern nightmares, it cannot heal the wounds which it reaches towards.

References

[1] Presentation of the Passion relics. Image taken from f. 11 of Illustrations for Mandeville's Travels. British Library, Additional MS 24189, fol. 11.

[2] Angel bearing a sponge, by Antonio Giorgetti, with the inscription “potaverunt me aceto” ("they gave me vinegar to drink", Psalms 69:22), western side of the Ponte Sant'Angelo à Rome.

[3] Huth Psalter. England [Lincoln or York?]; after 1280. British Library, Additional MS 38116, f.11v.

[4] Unknown artist after Antonio Giorgetti, Angel with the sponge, 17th century, gift of Dr J. Orde Poynton, 1959, Baillieu Library Print Collection University of Melbourne. Available online on page 3: https://museumsandcollections.unimelb.edu.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0008/2482154/02_Cole-Angel-sponge-19.pdf [Accessed 26th October 2025].

[5] Carrara Herbal c 1400. British Library Egerton 2020.

[6] Bibliotheque National Francais MS 16251, fol. 38r. Available online:

https://www.flickr.com/photos/looh01/11031615965/in/album-72157638011591754 [Accessed 26th October 2025].

[7] Hours of Joanna I of Castile, Flemish, early 16th century. British Library, Additional MS 35313, fol. 209r.

[8] Angels with the Instruments of the Passion. c. 1580. Orazio Farinati. Minneapolis Institute of Art. B.XVI.171.5/ii Nagler Mon.IV.5. Available online: https://collections.artsmia.org/art/50921/angels-with-the-intruments-of-the-passion-orazio-farinati [Accessed 26th October 2025].

[9] Psalterium ad usum ecclesiae Sarisburiensis, dit Psautier Fitzwarin 1301-1350. gallica.bnf.fr / Bibliothèque nationale de France. Département des Manuscrits.

Latin 765, f.14r. Available online at: https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b60005131/f29.item [Accessed 26th October 2025].

[10] Pablo Picasso, "The Crucifixion", 1930, Oil on canvas, 51.5 x 66.5 cm, Musée national Picasso-Paris, MP122. Available online: https://www.museepicassoparis.fr/fr/la-crucifixion [Accessed 26th October 2025].

EK Myerson is an artist and writer, currently studying for their MA in Contemporary Art Practice at the RCA. Their work explores medieval alchemy, transsexuality and Arab-Jewish history through film, sculpture, collage, curation, drawing and text.